Good decision-making comes from several key attributes, but critical amongst them is having good information: not so much that one is drowned in data, and not so little that you don’t know what’s going on. System 5, therefore, needs to be aware of inputs from systems 3 and 4 and make sure they are correctly balanced.

The role of System 5: Policy and strategic direction

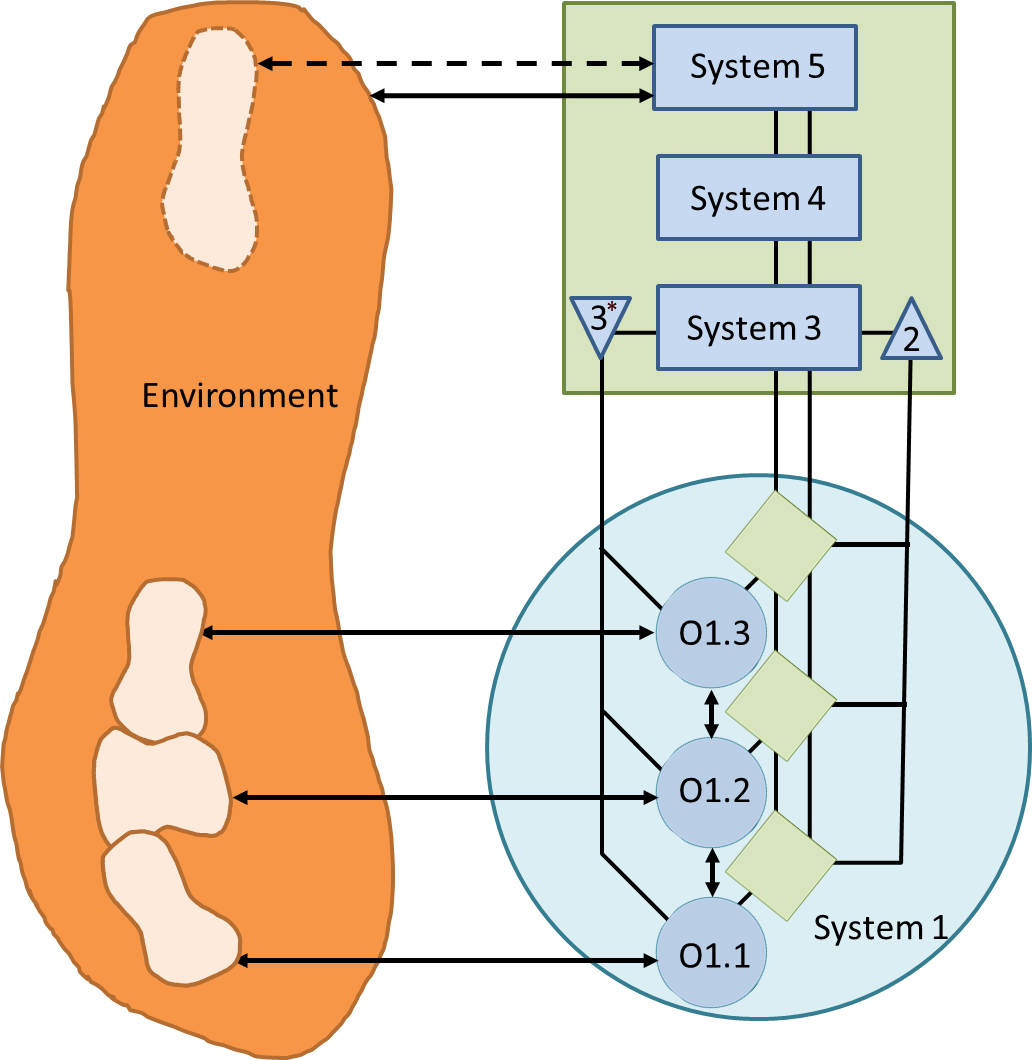

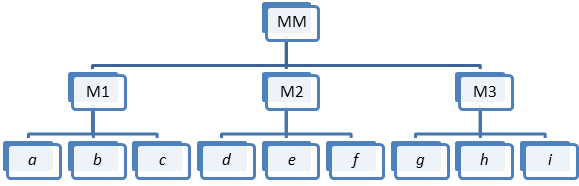

The VSM diagram (repeated here for convenience – click to enlarge) shows that system 5 is at the apex of the system, a bit like in an organisation chart where the CEO sits at the top. This doesn’t mean it’s the most important role. Remember this is a system model – everything is critical to the system – everything must play its part properly for the system to remain viable.Stafford Beer devoted several pages of his book Brain of the Firm to a discussion of why the hierarchical model of organisation structure, with the CEO at the top, is fallible and prone to failure. I have reproduced Beer’s org-chart here (click to enlarge): MM is the CEO role, M1, M2 etc. are middle layers of management and a, b, etc. are operational level. In a project management chart, the Sponsor chairs the Board (MM) with the board members being M1, M2 etc. and project teams being a, b, c, etc.. It will seem very familiar. Beer notes that this structure is “competent to apportion blame” [p.201], and Peter Scholtes describes this structure thus: “a fundamental premise of the ‘train-wreck’[1] approach to management is that the primary cause of problems is ‘dereliction of duty.’ The purpose of the organizational chart is to sufficiently specify those duties so that management can quickly assign blame” [The Leader’s Handbook, p. 4]

How does System 5 work?

The problem we have is: how can System 5 get all the right information without being flooded out by too much detail? This issue was central to a LinkedIn discussion starter I saw recently, that posed this question: “If you were a CEO and could only use one performance metric to guide the company, what would that metric be?”The originator of that discussion then went on to divulge his ideas, which centred around the common sense wish to include measures of value and the “velocity” of change in terms of what the organisation currently produces and what customers’ changing demands require (which he termed: velocity of value, or VOV).

At first glance this is an interesting idea because it appears to understand that “good” metrics are not single dimensional measures such as profit or cash flow. However, it reminded me of a story a wise teacher once told me about exam revision back in my school days (a long time ago!).

A student was studying a Shakespeare play and decided to make summary notes of all the aspects he needed to remember. The summary ran to ten pages of notes. “Too long”, he thought, so he summarised the summary down to five pages. Still too long. After several further iterations he ended up with a single word. He then went into the exam, having memorised this precious nugget and then found, when the Shakespeare question came up, he couldn't recall in enough detail the information he'd so condensed... and failed the exam.

It seems to me that leaders who want to so condense and summarise information about their organisation that they have one (or a very few) simple metrics to go on are making exactly the same mistake. And even though the VOV metric proposed by the originator of the LinkedIn topic is in fact a weighted combination of a number of contributor metrics, it isn't good enough. You simply cannot understand the workings of a complex organisation based on one measure! A good CEO will want to understand the complexity.

Balanced Scorecard

I then got to thinking about things like Balanced Scorecards, which seem to tackle this issue more effectively. The Balanced Scorecard, as originally envisaged by Kaplan and Norton, takes the view that financial measures alone are not enough to understand organisational performance. So they added additional dimensions (or perspectives): customer, business process and learning and growth as well as financial.Learning and growth looks at staff training and development (i.e. not just training) and at cultural attitudes at both individual and corporate levels. It tries to establish how well an organisation learns, and how it grows as a response to that learning.

The business process perspective, very crudely, looks at quality: how good we are at doing what we do. To use a Juran phrase: is what we produce “fit for purpose” from a customer perspective? And looking beneath the surface: what processes do we have to maintain our quality outputs?

Customer perspective is, hopefully, self-explanatory. Kaplan and Norton wrote about measuring customer satisfaction and customer focus. They noted that customer satisfaction is a leading measure (as opposed to financial measures, which are trailing measures). Personally I feel that customer satisfaction is not a true leading measure because by the time you pick up that customers are dissatisfied the situation has already arisen and they may already have left.

The Balanced Scorecard has much to commend it – not least the central idea that you need a balanced mix of information in order to understand your organisation’s performance, and hence make decisions about its future direction. But it is inextricably linked to the above idea of organizational structure.

Why the Balanced Scorecard is not enough

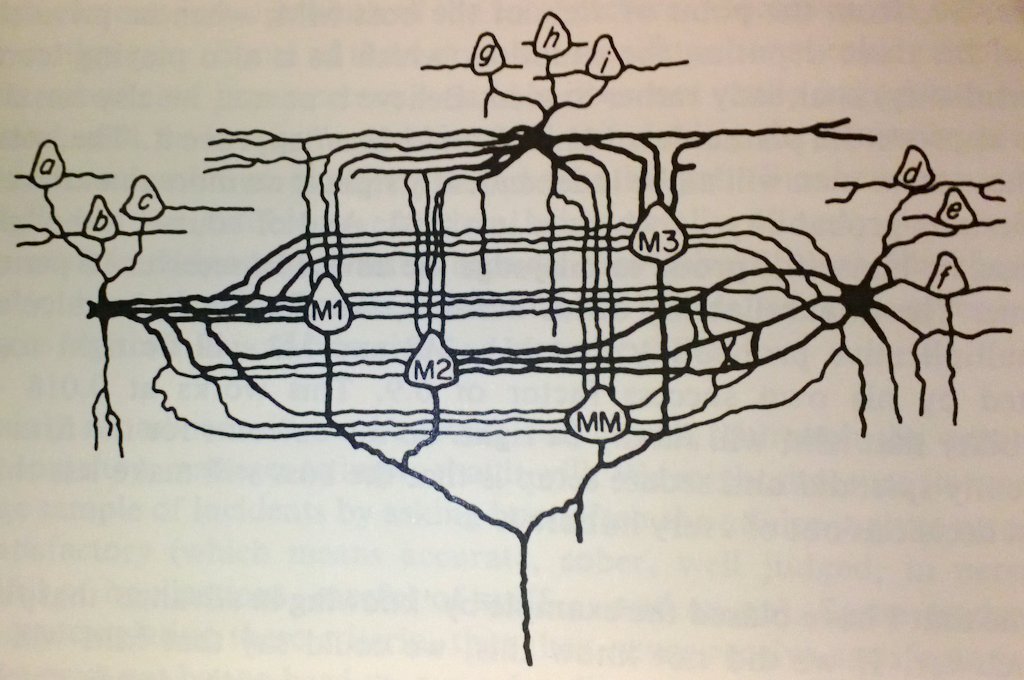

Returning now to Stafford Beer. In his discussion of organisational hierarchy he went on to sketch out how the human brain deals with decision making based on a multiplicity of information, and it looked nothing like the traditional org-chart above. Beer goes on to describe system 5 thus: “System 5 is not the collection of nodes, logically organized to be precise and well mannered, that our first model suggested. It is instead, whether made of neurons or managers, an elaborately interactive assemblage of elements. I call it the ‘multinode’.” [p. 205] His diagram of the multimode appears here (click to enlarge).The Balanced Scorecard is like the student’s revision summary and the neat organisation chart. It has the right idea: let’s take in a set of balanced information; but it fails because it tries to simplify too much in order to feed information along a single conduit to the decision making top-level process. What we need is Beer’s multimode where there are multiple pathways to the decision-making centre and also interconnections between the nodes that feed in to it. In other words, the underlying model of decision making is wrong!

I don’t have space here to go into exactly how Beer models the working of the multimode (he devotes twenty pages to this, including quite a lot of decision algebra). Suffice it to say that the system works because the nodes are all interconnected, and the evaluation that takes place at the nodes balances out to form an holistic model on an heuristic basis.

System 5 responsibilities

- Absolutely, to make strategic decisions;

- To ensure that inputs from both system 3 and 4 are taken into account when doing this;

- But not to do so in an autocratic, command and control structured way – a key responsibility is to ensure that the rest of the systems are in place so that sufficient information is received.

System 5 in projects

All of this has a major implication for the way Project Boards, and the project Sponsor, should behave.One the one hand I have seen Boards get too operationally involved. This is wrong because it would be like the brain wanting to consciously control the heartbeat. Chaos would result because we would neither be fleet of foot enough to properly control the heartbeat, nor free enough from all the work that would entail to keep a weather eye open on the rest of the system.

On the other hand I’ve seen Boards be too aloof. They hardly ever read the reports that come through from the project manager, or take time to understand the key issues in (just) enough detail to be able to make well-informed decisions.

I’ve also see project Boards where its members work to their own agendas.

Above all what the VSM tells us is that System 5 must concern itself equally with the system as a whole.

VSM lessons

Project Boards are too often like an afterthought: it’s almost as if the project works on its own without a Board, but has one stuck on because it is supposed to there! But then projects fail because they lack the high level decision making that’s necessary to keep them viable.This isn’t the end of my series on VSM and project management because we haven’t yet looked at the recursive nature of the model: within each operational node of the system (system 1) is a whole system of its own; and the whole system (the project) is itself embedded within a larger system. We’ll look at this next time.

Notes

[1] Scholtes used the train-wreck term because he was discussing this in the light of a real train crash disaster in 1841 that gave rise to this kind of management structure being created.

No comments:

Post a Comment